Current situation

Child abuse and neglect (CAN) constitutes a complex public health problem caused by numerous factors related to individual, family and community characteristics (WHO 1999; NIH 2007) and occurs in every country across all social, cultural, religious and ethnic population-groups, resulting in immediate and long-term social, health and financial consequences (Pinheiro 2006; Runyan et al. 2009).

Despite the importance of the problem, however, accurate estimates of its extent and characteristics in the general population –information which is necessary to inform planning and evaluation of prevention and intervention initiatives- are difficult to achieve because of two main interlinked problems: underreporting and under-recording of child abuse and neglect. There is sufficient evidence in international literature suggesting that large numbers of abused and neglected children are not coming to the attention of child protective authorities while, from those eventually coming to authorities a large part is not registered appropriately.

At a general population level, underreporting by children, parents and other laypersons is often observed because of a variety of reasons including the silence that surrounds cases of child maltreatment because of fear, shame, social stigma and the consequent criminal liability.

Underreporting of CAN by professionals working with and/or for children is also considerable, often concerning professionals who are mandated to submit reports when they have reasonable cause to suspect that a child is being abused or neglected. To a degree this is due to difficulty the professionals have to recognize child abuse and neglect. Defining child abuse more clearly, particularly in vaguely defined areas, and informing professionals for this definitions is expected to be of help for them to decide which cases to report. Better commonly agreed definitions of CAN incidents and types it may make professionals less hesitant and spark more reports; recording of reports in a uniform way following the same definitions would provide more reliable data for the magnitude, trends and special characteristics of CAN at local, national even international levels and, therefore, a robust basis for monitoring the problem and evaluating prevention and intervention initiatives.

On the other hand, underreporting is also observed for already identified CAN cases; one of the main functions of the US National Incidence Study (NIS) is to look at how much child abuse known to professionals still was not recognized by the child protection service agencies. Results showed that the majority of serious abuse known to professionals was not known by child protection services. In spite of increased reporting, the NIS shows an enormous reservoir of serious child abuse that is not reported. In 2005 Finkelhor noted that “although it is virtually impossible to count something so hidden [i.e. as underreporting of child abuse and neglect], most experts believe this quantity [i.e. of child abuse does not come to the attention of any professional] is also vast, probably two to three times higher than those currently reported. All of this suggests a major problem of underreporting.”

Needs to be addressed

Reporting of CAN cases is strictly related to recording; by definition, underreporting is in general a failure in data reporting; concerning CAN, underreporting refers to cases or suspected cases of CAN which for some reason were not reported to appropriate authorities by individuals (including professionals) or relevant agencies. Systematic recording of CAN cases, namely systematic data collection, reflects the amount of reported cases in relevant authorities; uncoordinated recording practices may provide a picture about reporting practices worse than in reality, while under specific conditions improvement of recording may be translated as increased reporting (as for example when systematic recording is starting in a place for first time). In this context, lack of systematic recording of reported CAN cases by relevant sectors working with and for children at a local or national level, do not allows the estimation and monitoring of the quantity of underreported CAN cases; this is why magnitude of underreporting is often an issue of consensus among experts in the field rather than a precisely measured amount. Moreover, changes in reporting trends as well as in CAN incidence trends cannot be traced due to the lack of relevant recording mechanisms.

The necessity for data collection on child abuse and neglect is a commonly accepted priority worldwide and in the EU countries in particular. Therefore, the necessity for child maltreatment surveillance mechanisms that provide continuous and systematic data to monitor the magnitude and impact of CAN is undeniable. However, in EU it is a fact that child abuse and neglect case-based data are often derived from a variety of inter-sectoral sources involved in the administration of each case, and follow up of victims at local and national levels is not sufficiently coordinated among the involved services. This is also obvious in the General Comment 13 (2011) of the UN CRC where it is noted that “[…] The impact of measures taken is limited by lack of knowledge, data and understanding of violence against children and its root causes, by reactive efforts focusing on symptoms and consequences rather than causes, and by strategies which are fragmented rather than integrated.”

Main barriers for effective administration of CAN include: difficulties in recognition of CAN by professionals working with and for children; underreporting -even from mandated professionals; lack of common operational definitions; weak follow-up at a case level; lack of common registering practices and the use of a variety of methods and tools for collection and sharing information among stakeholders. Due to insufficient registration of CAN reports follow up of cases at local and national levels is not sufficiently coordinated among the involved sectors. At an international level, where currently monitoring systems exist, they vary considerably, so that comparisons are not feasible; reliable data, however, are crucial to end the invisibility of violence, challenge its social acceptance, understand its causes and enhance protection for children at risk; data are vital to support government policy, planning and budgeting for universal and effective child protection services, and to inform the development of evidence-based legislation, policies and implementation processes.

The Policy guidelines on integrated national strategies for the protection of children from violence, released by the Council of Europe in 2009, aim to promote the development and implementation of a holistic national framework to safeguard the rights of the child and to eradicate violence against children. They are based on general principles, for example, the best interests of the child and the protection of children from violence as well as on operative principles where the integrated approach is advocated along with cross-sectoral co-operation and multi stakeholder approach. Moreover, in Investing in children: the European child maltreatment prevention action plan 2015–2020 (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2014), the first objective focuses in making “health risks such as child maltreatment more visible by setting up information systems in Member States”, while the second objective states that “substantial gains in preventing child maltreatment can be made by coordinating actors in multiple sectors”. Inter-sectoral and multidisciplinary collaboration is of crucial importance for tackling effectively child maltreatment. To this direction, data collection is advocated throughout General Comment No. 13 (2011) of the Committee on the Rights of the Child; in relation to effective procedures, recommendations were included regarding “inter-sectoral coordination” and “development and implementation of systematic and ongoing data collection and analysis” (Art. 57. a,b,d).

EC, in particular DG-Justice prioritizes data collection activities relevant to the rights of the child. During the 7th EU Forum on the rights of the child insights were gained into some of the gaps within integrated child protection systems, such as that available data are not yet good enough to support evidence-based policy making. In the conclusions of the 8th Forum the need for and value of integrated child protection systems were underlined providing that such systems can effectively address diverse protection needs of children in all circumstances through enabling diverse actors to collaborate with each other, coordinate their actions across different sectors, and use a variety of tools and measures to address violence and abuse. In the 9th Forum, “integrated child protection system” was defined as “the way in which all duty-bearers and system components work together across sectors and agencies sharing responsibilities to form a protective and empowering environment for all children”. Such a system places the child at the centre, putting in place laws and policies, governance, resources, monitoring and data collection, as well as prevention, protection, response services and care management while “components and services are multidisciplinary, cross-sectorial and inter-agency, and they work together in a coherent manner”. As is mentioned in the 10 principles discussed at the 9th Forum, professionals working for and with children should receive training and guidance on children’s rights, relevant laws and procedures in order to be committed and competent; to facilitate their response to CAN, applied protocols and processes should be inter- or multidisciplinary; standards, indicators, tools and systems of monitoring and evaluation should be in place “under the auspices of a national coordinating framework” and child protection policies and reporting mechanisms should be in place within organisations working directly for and with children (Principle 6). Moreover, safe, well-publicised, confidential and accessible reporting mechanisms should also be in place, available for children, their representatives and others to report CAN, including through the use of 24/7 help lines and hotlines (Principle 10).

UN concluding observations

Petrowski (2010) noted that “the development of a national child maltreatment data collection and monitoring system that is reliable, accessible, and comparable is not only viewed as good practice, but is also a legally binding responsibility of State Parties that have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC; UN General Assembly, 1989)”. Therefore, “it is compulsory that States tackle the phenomenon of child abuse through a comprehensive approach to tracking, monitoring, preventing, intervening/treating, and providing supports and resources”. In its concluding recommendations addressing EU countries, the UNCRC almost always recommends that member states undertake initiatives in order to improve data collection related to children’s rights in general and to child maltreatment in particular depending on the progress of each country.

CAN-MDS Feasibility Study in EU28: In this study (2015) 137 representatives from 15 EU countries were participated. Respondents were requested to provide estimations of the current situation in their countries concerning, among others, their knowledge of the magnitude of CAN and the status of cooperation among and within sectors on CAN cases. The results in five of the six countries participating in this project (BG, FR, EL, RO and ES) showed that the knowledge on the “magnitude of CAN at a national level” was estimated as not sufficient (mean 47/100); estimations of awareness about “specific forms of CAN at a national level”, “CAN at a regional level” and “changes over time” were also low (41, 47 and 27/100 respectively), indicating that there is ground for improvement; lack of such knowledge indicates underreporting of CAN cases but does not allow estimations about the scale of underreporting. Concerning the status of cooperation among and within sectors (inter-disciplinary and inter-sectoral cooperation) estimations provided by the respondents were also low. Specifically, concerning the extent that “inter-sectoral (welfare/ (mental) health/ justice/law enforcement/education) cooperation routes for administration of CAN cases” in place were estimated at 50/100 and, similarly, mean estimation for “cooperation routes among different-sectors professionals involved in administration of the same CAN case” was low (52/100). Inter-agency cooperation within health sector was estimated by mean at 35/100 (and 29/100 for mental health); within law enforcement at 43/100; within justice sector at 47/100; within welfare sector at 47/100; and within educational sector at 48/100. Therefore, inter-sectoral and multi-disciplinary cooperation on cases of CAN still needs improvement.

Target group are professionals working directly and/or indirectly with children in sectors relevant to child protection and wellbeing such as welfare, hotlines, health and mental health, education, law enforcement and justice, governmental or relevant NGOs. According to the 9th of the 10 Principles for integrated child protection systems (EU DG Justice and Consumers, 2015) training is needed to be delivered on identification of risks for children in potentially vulnerable situations to professionals such as teachers at all levels of the education system, social workers, medical doctors, nurses and other health professionals, psychologists, lawyers, judges, police, probation and prison officers, residential care givers, civil servants and public officials, and asylum officers. Child protection systems in 6 countries are expected to be immediate benefit from the project’s results while main beneficiaries, namely children (victims or at risk of CAN) and their families as well as the general population are expected to be benefit over the time.

CAN-MDS Policy Recommendations

European Countries [English]

BULGARIA [Bulgarian]

CYPRUS [Greek]

GREECE [Greek]

ROMANIA [Romanian]

SPAIN [Catalan]

- CAN-MDS Policy Brief Series

2019

- BULGARIA [Bulgarian]

- CYPRUS [Greek]

- FRANCE [French]

- GREECE [Greek][English]

- ROMANIA [Romanian]

- SPAIN [Catalan]

2021

CAN-MDS Policy Brief (European level) [English]

______________________________________________

PREVIOUS PROJECT'S OUTPUTS

- CAN-MDS Policy & Procedures Manual (EN)

- CAN via MDS: Informational Leaflet (EN)

- CAN surveillance in European Countries: Current Policies and Practices

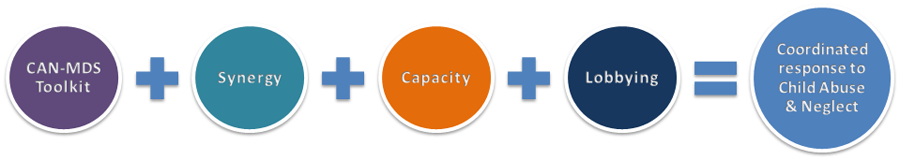

- CAN-MDS master Toolkit and Methodology for adaptation

- CAN-MDS Data Sources and Operators Eligibility Criteria

click here to see and download CAN-MDS products